At the recent Health 2.0 conference, I heard a speaker talk about how hard it is to get doctors “to learn population health” and how other types of personnel – care managers or office administrators – might best be tasked with this function. This reminded me of Dr. Lipton, our family physician from the 1950’s and 60’s for whom what we now call population health was just the way he practiced medicine.

Dr. Lipton got paid for professional services rendered, in cash, on a fee schedule and sliding scale. But he also worked to earn our trust and there was no doubt that this was an important form of compensation for him. His value proposition was three fold: mastery of his craft, demonstrable commitment and genuine consideration - and to his mind, his responsibilities for our health extended beyond the doors of his office.

Dr. Lipton got paid for professional services rendered, in cash, on a fee schedule and sliding scale. But he also worked to earn our trust and there was no doubt that this was an important form of compensation for him. His value proposition was three fold: mastery of his craft, demonstrable commitment and genuine consideration - and to his mind, his responsibilities for our health extended beyond the doors of his office.

If my grandfather – who had his first heart attack in his mid-30s – missed his quarterly blood pressure check, we would get a call. After my grandmother’s sigmoidoscopy, he stopped by the house. And after my mom had a bout of anxiety, his nurse called every few weeks for a while to see how she was doing.

Time and time again he demonstrated to us that we were very present in his life even when we were absent from his waiting room. And his technology for this: the work of worry. His compensation for the work of worry was nothing more than social capital.

For us, he provided mental comfort -- a safe harbor, despite looming threats — because there was a person, and not just a person, an expert, who worried along with us and that was in many ways a more important influencer of our healthcare quality then the medicines he prescribed.

I am not making a case to return to these days – though this does sound remarkably like that ‘new model’ of direct patient care. No I am raising this because I worry that we’ve fragmented the concept of quality and in doing so, allowed the “how” to obscure the “why” for care delivery… When someone say ‘quality’ these days, I am reminded of the classic story of an elephant described by a group of blind men; measures of quality are a function of your viewpoint: it's a rope, it's a wall, it's a pipe; it's gaps in evidence–based care, error reduction, functional status, a method to save money, a method to make money and of course what professionals think they do every day.

The real challenge is that health – and therefore our ability to influence health status -- is complicated by being influenced by so many different variables in a person’s life. To date, our approach to technology has largely been to pick one level of the system and design technologies to help us better manage variables at that level.

The problem with this approach is, like in a game of three-dimensional chess, a move that may make sense at any one level may actually be irrelevant or counterproductive in light of factors at the levels above and below.

Our healthcare technology focus on these “controllable” variables illustrates the fact that most of our current technologies are designed from a very left-brain perspective – logical, sequential, rational, analytic, and objective. Yet, it is well established that health, healing and care giving is really very much driven by our right brains: connected, feeling, nonverbal, holistic, and subjective.

Which means that if we truly want transform care delivery with technology we need to shift our focus from the meaning of the data to what we mean to each other.

A sustainable change in healthcare quality will require technology designed around a deeper understanding of the multi-factorial nature of both the quality of health of individuals and the quality of care we deliver to them. And when I need to understand dynamic multi-variable systems I usually turn to an expert, like Sir Issac Newton.

You see, after all these years I discovered why calculus was a prerequisite to medical school…because calculus is the study of how things change. It’s a framework for understanding dynamic systems and the effects of changing conditions, positions and functions on those systems.

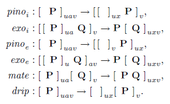

With this in mind, I propose a new model for how we consider healthcare quality: the quality calculus.

The quality calculus is a new way to understand health and illness and would permit us to design and test new kinds of care delivery based on the unique limits of variables for an individual (including, social capital) and also allow us integrate these variables to reveal the dominant factors and that influence the health of the population at a particular point in time.

The quality calculus also provides a foundation for new technologies. Here we will need to move beyond data and analytics and design applications that don’t just fit into the workflow, but belong to the thoughtflow – technology that amplifies the humanness in our care delivery and allows people to find meaning and value within themselves and from each other.